Berthe Jansen

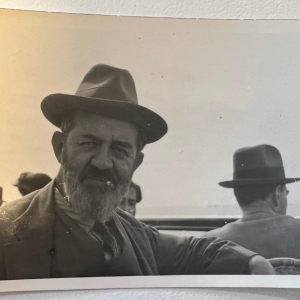

2nd draft Blog 1 A Dead Dutch Tibetologist A Dead Dutch Tibetologist, a Live One, and a Whole Bunch of Boxes : The Van Manen Project AFTER STROKE MORNING FIFTEENTH DIED INTESTATE HOSPITAL UNCONSCIOUS WITHOUT SUFFERING MORNING SEVENTEENTH BURIED [..] DEEPLY MOURNED NUMEROUS FRIENDS ALL STAGES LIFE stop [..] DEATH BROADCASTED ARTICLE STATESMAN stop ONE YOUNG DEVOTED CHINESE SERVANTBOY ALRIGHT stop [..]POSSESSIONS INDIA SCHOLASTIC BOOKS PERSONAL EFFECTS ONLY stop I HAVE APPLIED ADMINISTRATION ESTATE (excerpt from telegram informing Van Manen’s sister of his death) Unfinished business It is perhaps the dread of every scholar: to die with all manner of papers, articles, and books – many of which the deadline had passed long before death itself – unfinished and unpublished. Worse still may be the mess a dead academic leaves behind. Who is equipped to sort it out? As I sift through the 26 archival boxes containing the texts, manuscripts, but also what appears to be the contents of the desk that is the inheritance of the Dutch Tibetologist (1877-1943), I quietly pray that I may live long enough to complete all my pending research projects. Since I was awarded an in 2023, I now have another one to add to the list: to study the Van Manen collection, and – with the risk of sounding grandiose – to finish what the Dutchman had started, almost exactly 80 years after he died a sudden death, leaving all worldly possessions behind. What is a collection anyway? Before encountering the Van Manen collection, I never really wondered why people collect – or simply accrue – what they collect. Johan van Manen ended up with over . The whole collection was bought by the ethnographic museum in Leiden (recently renamed Worldmuseum) and has been housed in that university town since the early 1950s. The texts have been catalogued a few times, and most of them were even scanned and are now digitally available. The desk contents, the ephemera so to speak, have not yet been assessed fully. Let alone scan. The scans do allow the scholar to access the individual texts, sure, and it is even greater they are also linked through to . But what of the whole collection as a collection? The way I see it, and I am sure I am not the first person to come up with this, a collection is – at least – two things: 1) a reflection of a person’s interests 2) a reflection of what was available at a certain time and place. The two things are of course very dependent on each other. Can we then, by looking at the collection as a whole, understand the processes of cultural production of the region(s) the works were produced in? May this kind of investigation tell us something of the availability of these works? The printeries the texts were produced in, the workshops the artifacts were made in, the more obscure texts Van Manen’s assistants borrowed to copy by hand. The challenges here should be obvious: the printeries’ names are in most cases not given on the blockprints themselves, the workshops anonymous, the originals of the copies lost to the elements. This is where the detective work starts – the ephemera that were preserved: Van Manen’s notebooks, correspondences, receipts, and inventories are definite leads. The autobiographies that he had asked (or commissioned) his Himalayan assistants and friends to write for him contain further clues. Some of them even traveled to Tibet and other places to buy texts and materials for him, shopping list in hand. (A blog post on a shopping list Van Manen made for a Tibetan scholar monk to take to Lhasa is upcoming, btw!) Unbox and decolonize? A collection can sadly also be a lot more than a combination of a person’s interest and the availability of objects. Increasingly these days, objects collected in the 19th and early 20th centuries in lands once colonized are implicated in theft, unfair acquisition, or other unethical ways of obtaining things . Things that were (later) deemed to be of religious or national importance. Scholars now work with those affected by colonization to unearth the collections’ dark pasts and repatriate objects when and where necessary. And rightly so. There is a danger, however, that we come to see everything collected in those times, in those regions, to be problematic by definition. What of Van Manen’s Himalayan texts and objects then? Van Manen bought – or had others buy for him – items in Tibet, Nepal, and current-day India. As a Dutch citizen, he was not directly part of the colonial regime, but of course worked closely with others who were. A further complicating factor is that the Himalayas as a cultural and geographical region have a present that is equally complex, if not more so, than its past. Who and where do you repatriate to? You can see that we, in this ERC project, have our work cut out for us. This is just the first blog of many yet to come: about our journey through the archives, our fieldwork, and our research. We plan to reveal the tiny gems that this collection contains, but also the important finds that we hope to be able to bring to light. One of the last photographs taken of Van Manen (Nationaal Archief, Panthaleon Van Eck collectie) The telegram sent to Van Manen’s sister, Charlotte van Manen. (Nationaal Archief, Pantheon Van Eck collectie)